Genomic Imprinting

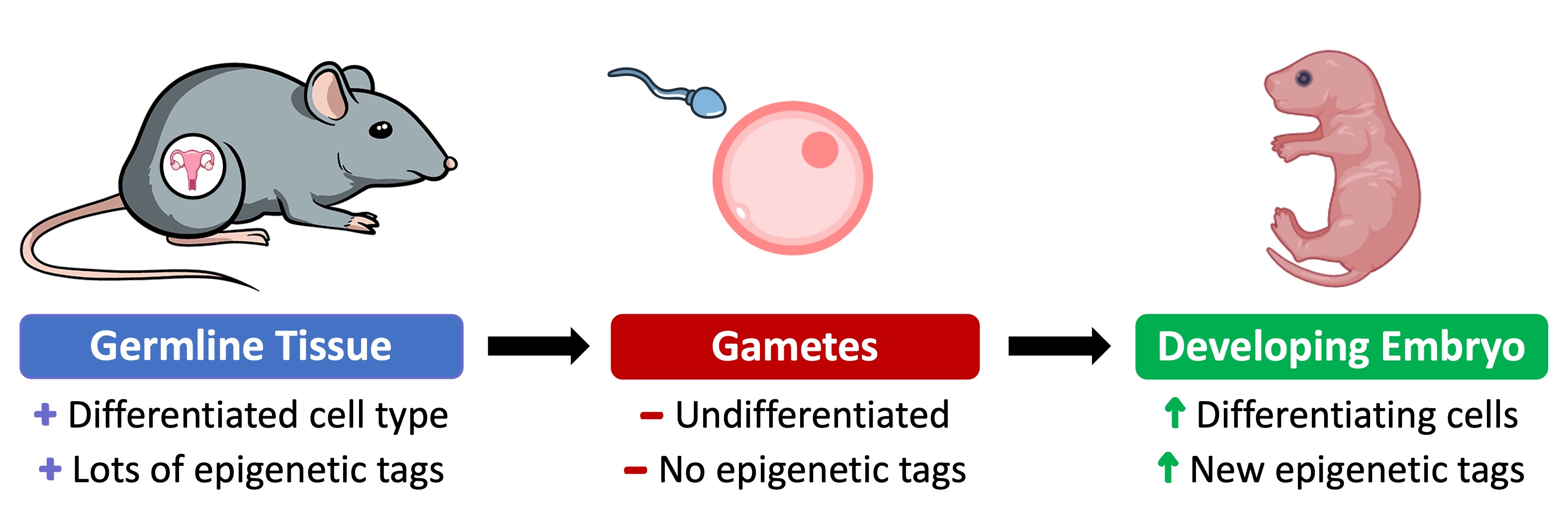

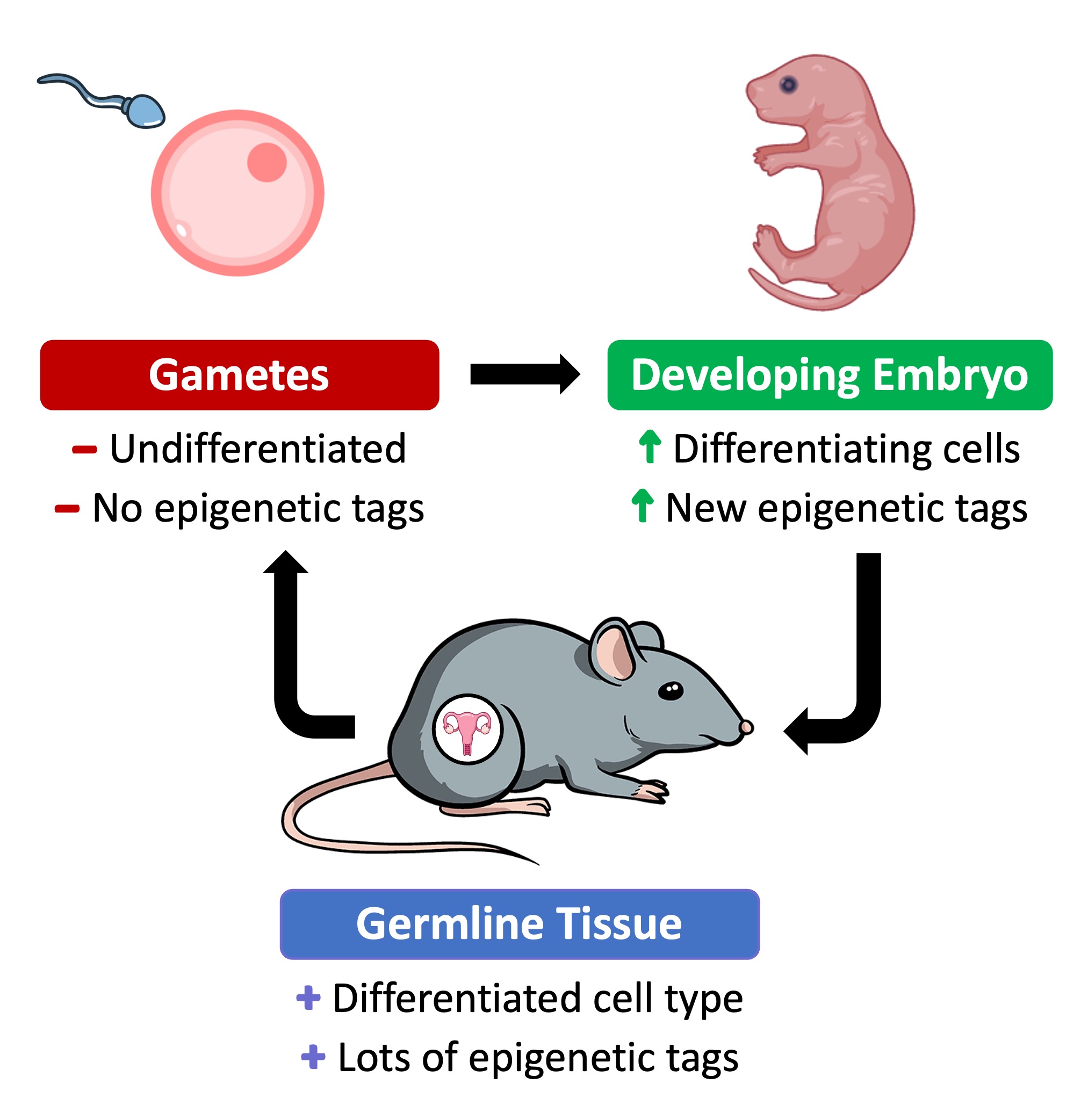

Most complex organisms develop from undifferentiated cells as a consequence of the programmed expression of genes via epigenetic tags

-

Different genes are switched on or off in specific cells to promote the development of distinctive cell lines (tissues)

-

This progressive development of a complex multicellular organism from an undifferentiated pluripotent cell (zygote) is called epigenesis

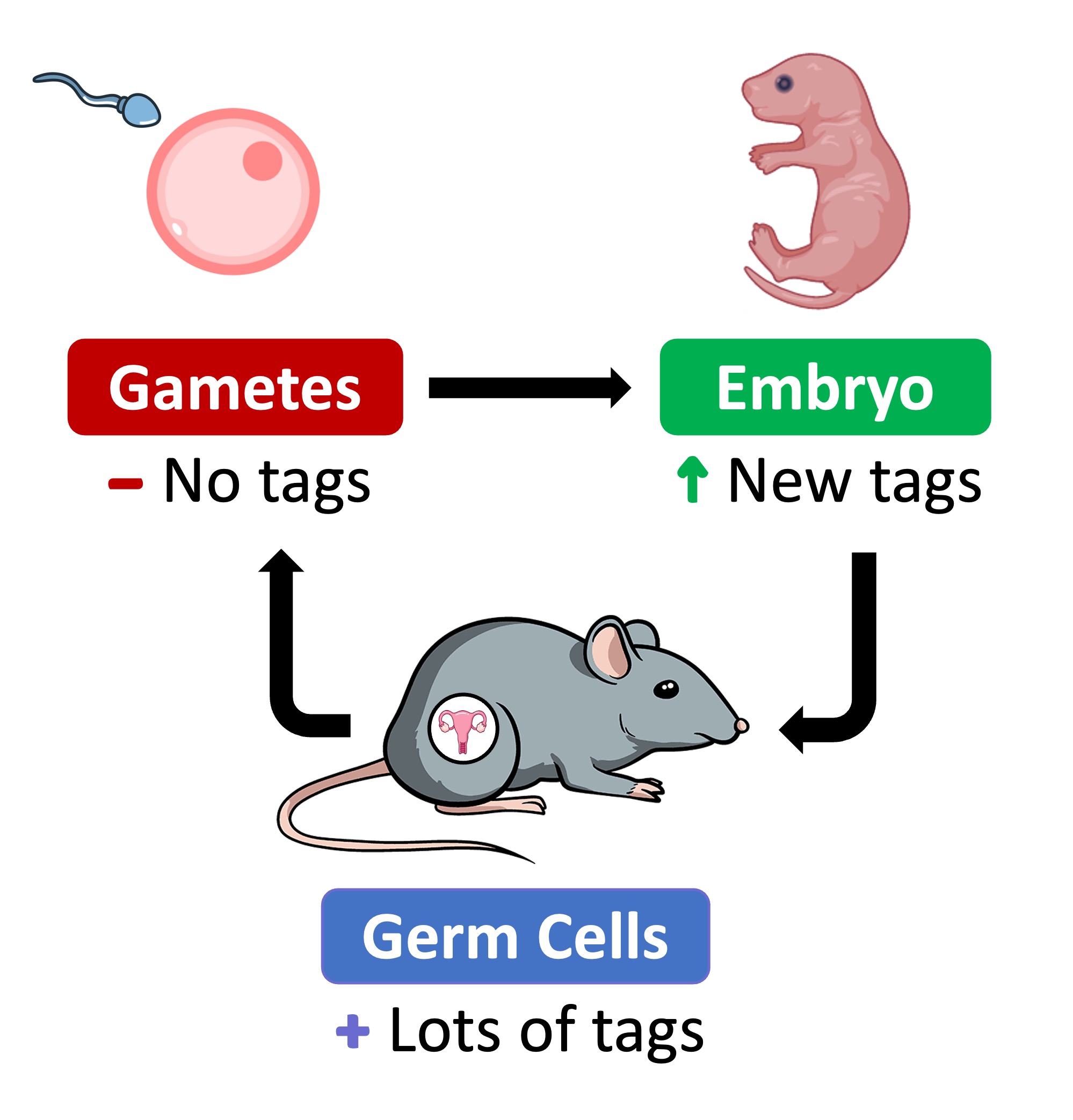

As egg and sperm cells develop from differentiated germline tissue, the pre-existing epigenetic tags in these cells must be erased to allow for epigenesis to reoccur upon fertilisation

-

The reproductive cells must be reprogrammed via epigenetic tag removal to return the gametes to a genetic 'blank slate'

-

Reprogramming ensures that the early embryo can form every type of cell in the body by resetting the epigenome

-

The presence of pre-existing epigenetic tags is believed to be responsible for the low levels of success experienced when cloning animals from adult cells (via somatic cell nuclear transfer)

-

Normal Epigenetic Inheritance

Imprinted Genes

A small proportion of genes do not undergo reprogramming during gamete production and remain epigenetically silenced in the egg or sperm

-

Different genes may remain silenced in sperm cells versus egg cells, resulting in only one active copy of these genes in the offspring

-

Genes that retain their epigenetic tags are called imprinted genes and allow for phenotypic changes in an organism to be potentially passed on to offspring

The inheritance of imprinted genes has several significant biological consequences:

-

Mutations: Imprinted genes typically have a higher mutation rate as methylated DNA is susceptible to deamination (C → T)

-

Evolution: As imprinted genes have only one active copy they are more vulnerable to selection pressures, leading to higher rates of evolution

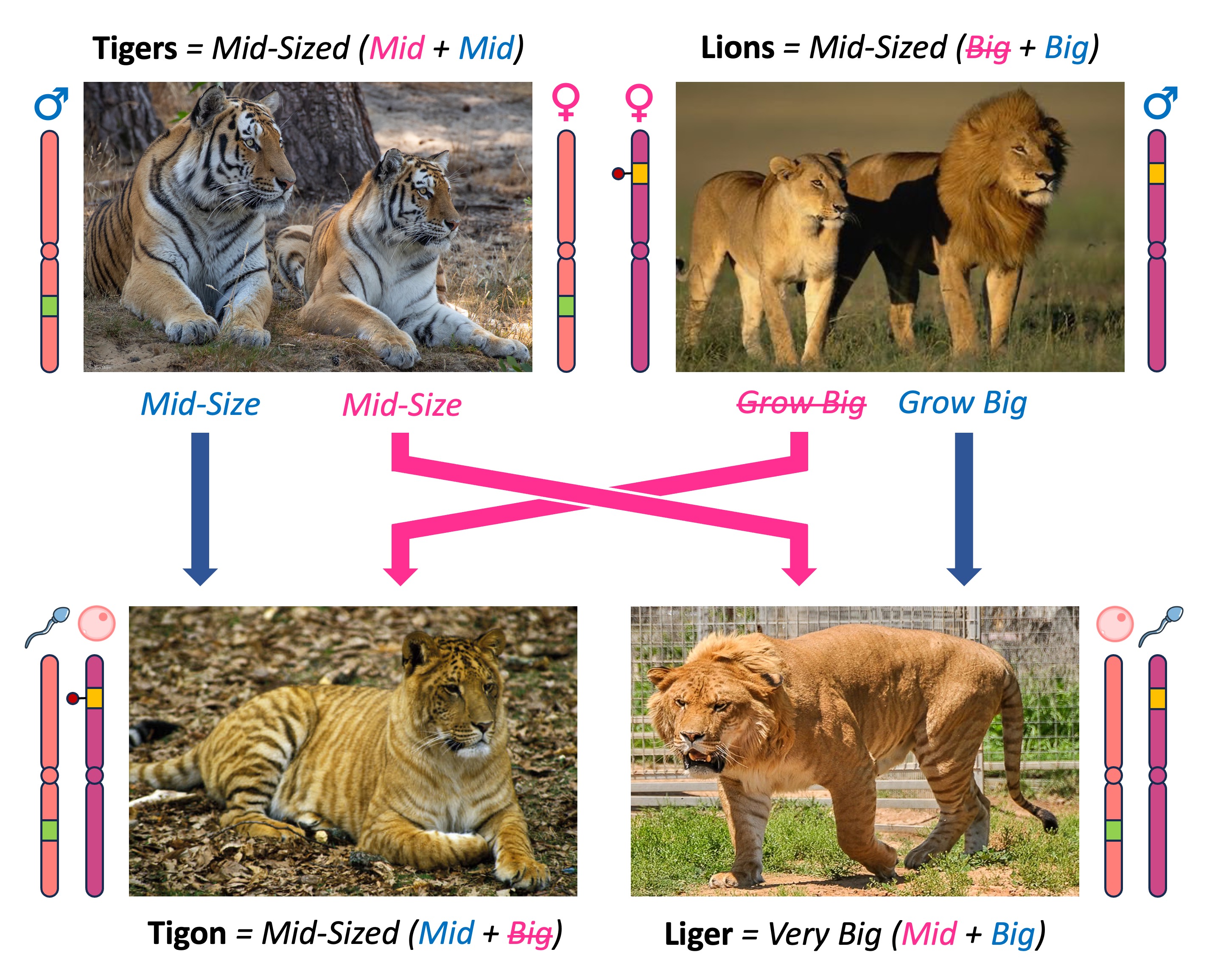

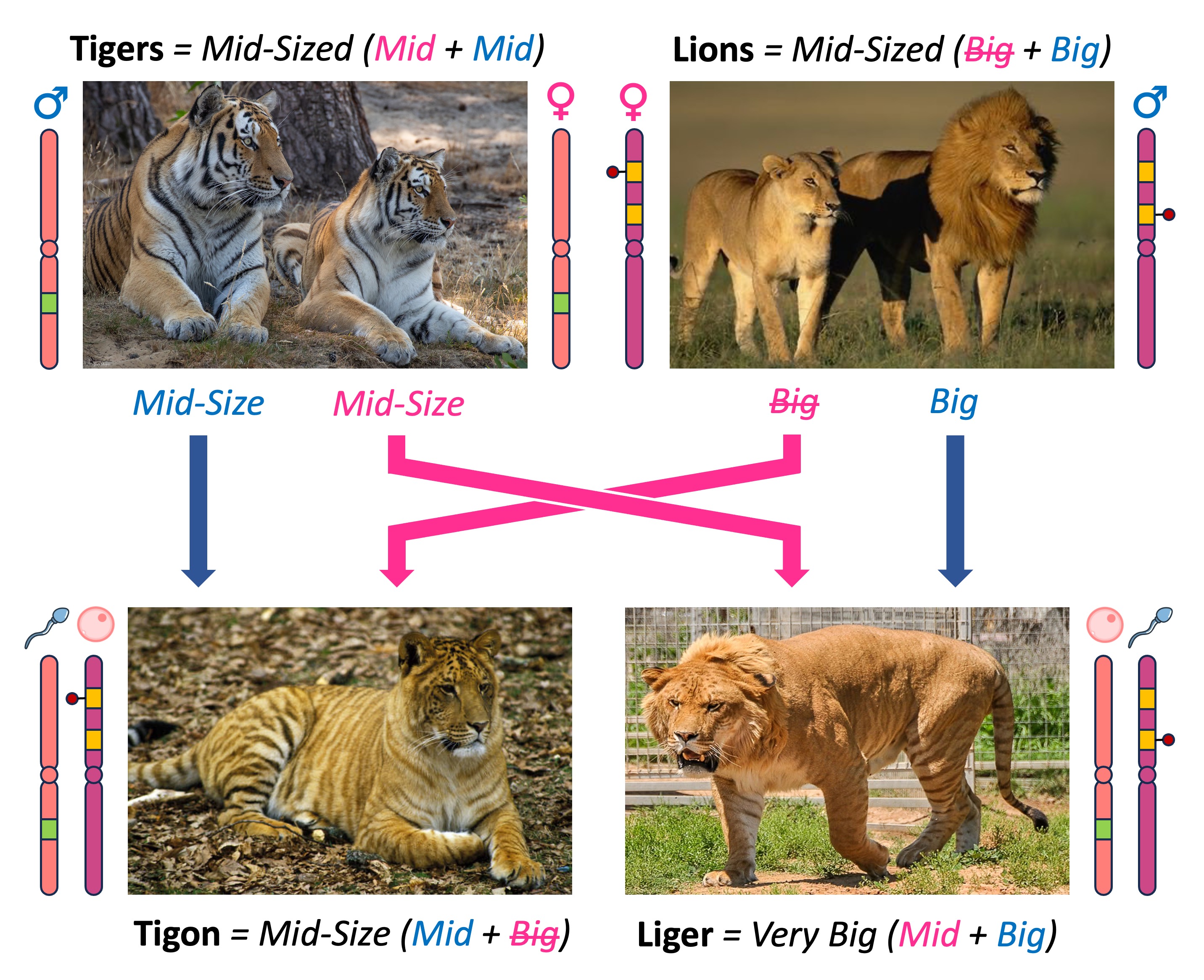

Hybrid Species

The retention of certain epigenetic tags within the ovum or sperm is thought to be responsible for the size differences seen in ligers and tigons (lion-tiger hybrids)

-

Ligers (offspring of a male lion and a female tiger) are the noticeably larger than both lions and tigers

-

Tigons (offspring of a male tiger and a female lion) are roughly the same size as an average lion

Lions live in social groups (called prides) whereby a single lioness may mate with multiple males and have a litter with cubs from multiple fathers

-

A male lion is therefore incentivised to have the largest offspring (in order for his cubs to outcompete the other littermates) and hence will produce sperm containing imprinted genes that promote growth

-

However, the lioness is incentivised to have smaller offspring (in order to achieve a successful pregnancy that prioritises all cubs equally) and will produce eggs containing imprinted genes that restrict growth

-

The combination of these imprinted genes cancel each other out and result in lion cubs that are mid-sized

Tigers are solitary animals and a tigress will only produce a litter with cubs from a single male tiger

-

Consequently, the reproductive goals of the male tiger and female tigress are the same and there is no need for imprinted genes to develop in this species

When a lion and tiger successfully mate, the different imprinting strategies of the male and female lion determines the size of the offspring

-

In ligers, the lion sperm (imprinted to promote growth) was combined with the tiger egg – resulting in large offspring

-

In tigons, the tiger sperm was combined with the lion egg (imprinted to restrict excessive growth) – resulting in normal sized offspring

Ligers versus Tigons