Gene Mutations

A gene mutation is a change in the nucleotide sequence of a section of DNA that encodes for a specific trait

-

A change in gene sequence may alter the polypeptide sequence, leading to alternative forms of a protein

-

These alternative forms may result in new functionalities (e.g. new alleles) or abrogate normal activity (e.g. genetic diseases)

Mutation rates are not constant and may differ according to the gene and organism (or organelle) involved

-

When a single specific nucleotide is changed in a sufficiently large proportion of the population (typically >1%), it is called a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)

-

By comparing the SNP pattern in people with a genetic disease to those that are healthy, it is possible to identify genetic markers (and potential causes) for the disease condition

Causes of Gene Mutations

Gene mutations can be caused by proofreading errors during DNA replication or by mutagenic agents

Proofreading Errors

-

During DNA replication, the enzyme responsible for copying the DNA sequence (DNA polymerase) will automatically detect and remove any incorrectly paired nucleotides

-

If the polymerase fails to reverse the incorrect pairing, the offending nucleotide can still be replaced after DNA synthesis is completed via a process known as mismatch repair

-

If a damaged or incorrectly incorporated nucleotide is not replaced it will alter the DNA sequence, resulting in a gene mutation

Mutagens

-

A mutagen is an agent that induces a permanent change to the genetic material of an organism (increasing the frequency of mutations above the natural background level)

-

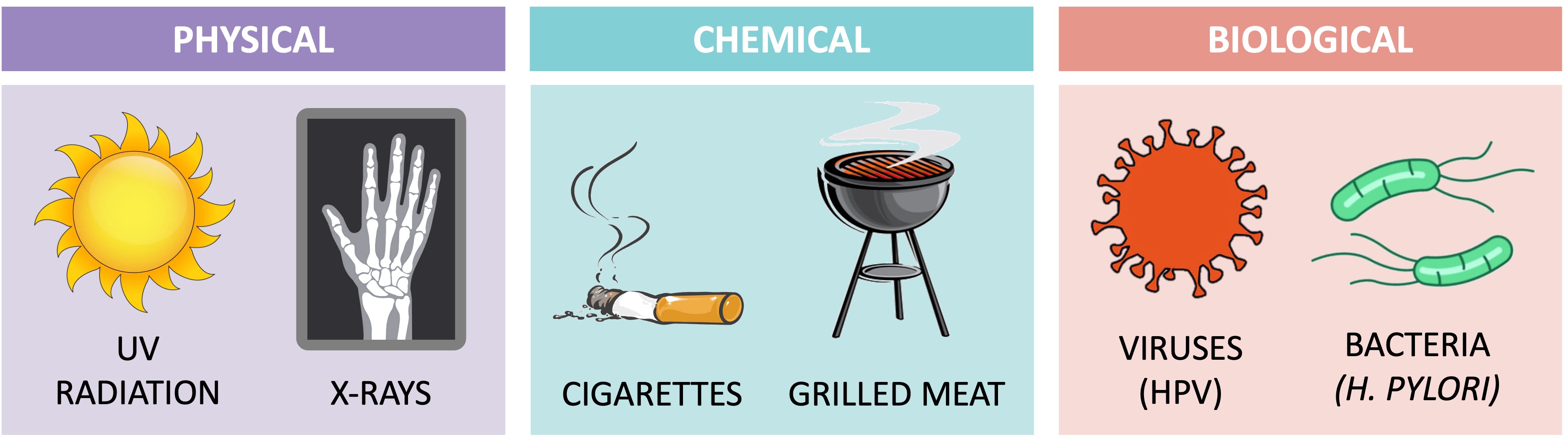

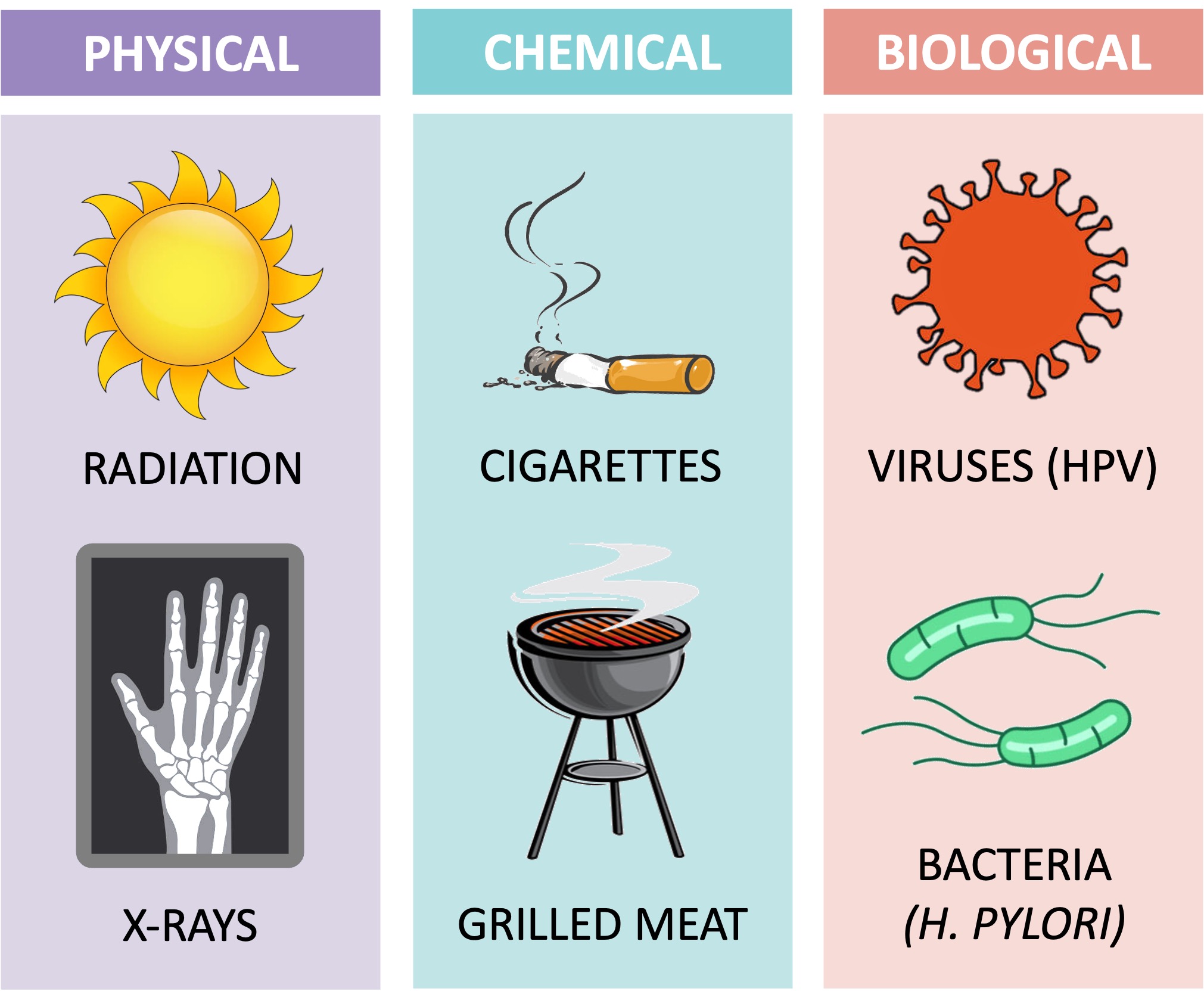

Mutagens may be physical, chemical or biological in origin:

-

Physical: Certain forms of radiation, including X-rays and ultraviolet (UV) light

-

Chemical: Substances such as reactive oxygen species, certain metals (e.g. arsenic) and alkylating agents (which can be formed by grilling meat)

-

Biological: Some viruses (e.g. HPV) and certain bacteria (e.g. Helicobacter pylori) can induce mutations

-

Types of Mutagens