Adaptive Immunity

The third line of defence against infectious disease is the adaptive immune system, which has two key properties:

-

It can differentiate between specific microorganisms and respond accordingly (it is specific)

-

It can adapt and produce a heightened response upon re-exposure (it has memory)

The adaptive immune response is slower to mobilise and involves a specific type of white blood cells called lymphocytes

-

B lymphocytes produce antibodies (they are the workers), whereas helper T lymphocytes activate the B cells (they are the supervisors)

Clonal Selection

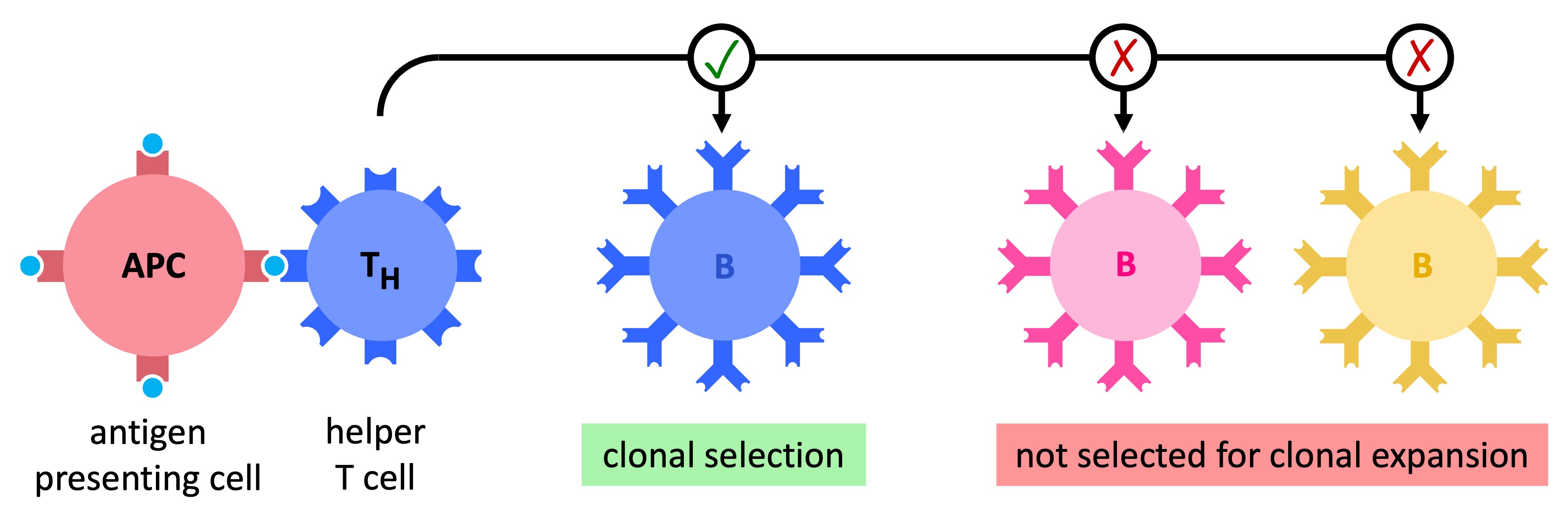

Every individual possesses a very large number of distinct TH and B lymphocytes that each recognise and respond to a particular antigen

-

Only the B lymphocytes that are specific to a given antigen will be able to directly interact with the associated pathogen

-

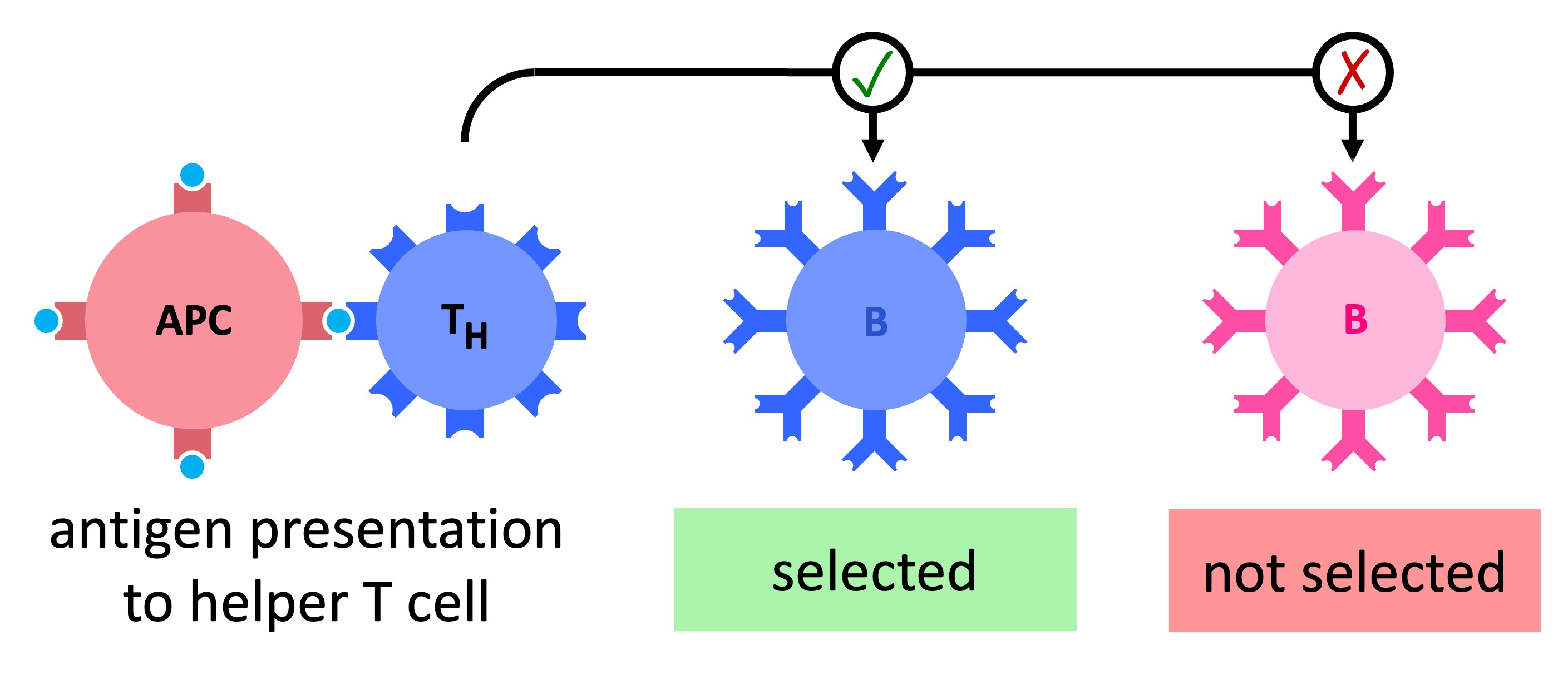

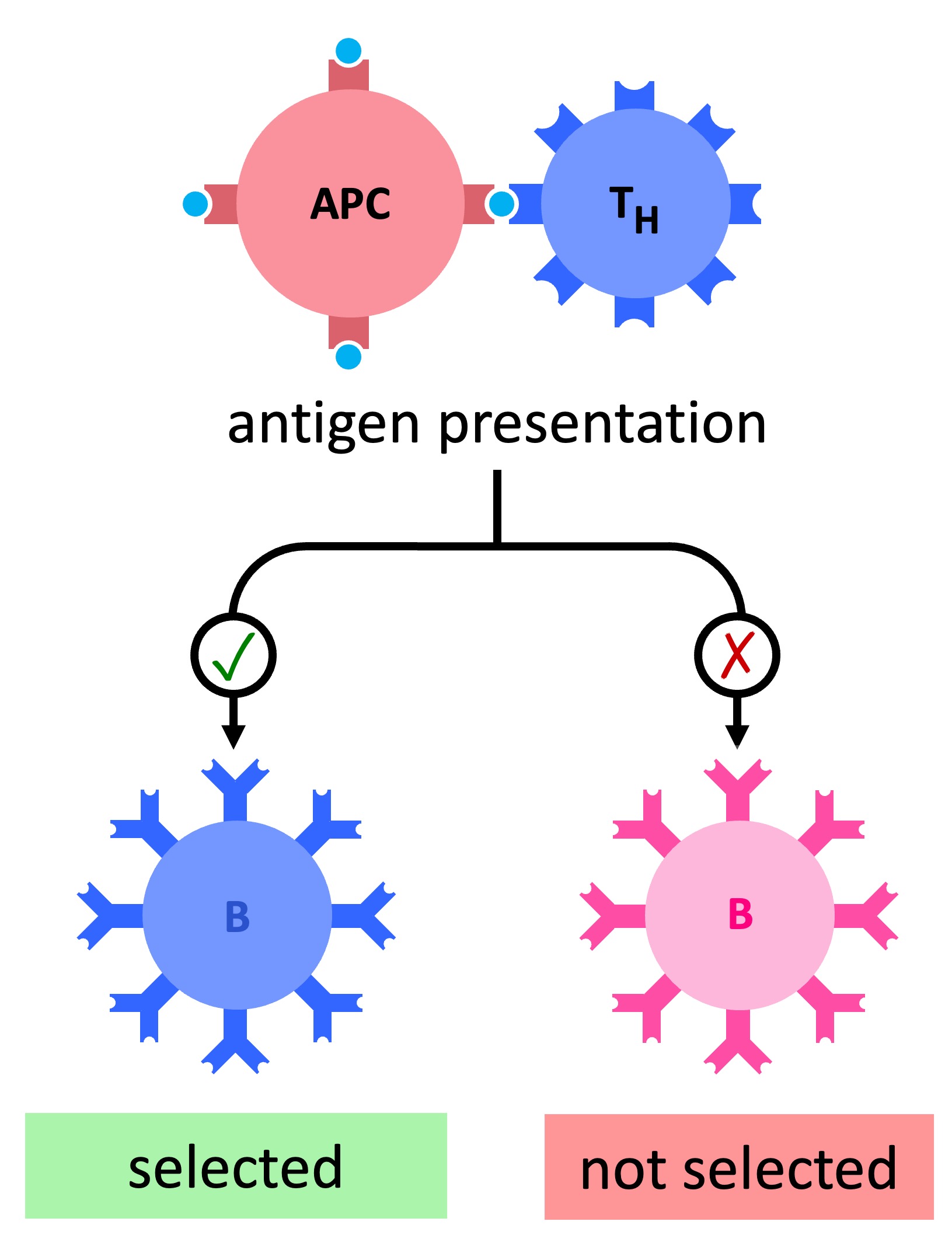

TH lymphocytes do not interact with pathogens directly – they need to be introduced to the antigens by the antigen presenting cells

When a helper T lymphocyte is activated, it forms a complex with the appropriate B lymphocyte and releases cytokines

-

The cytokines stimulate the specific B cell to divide and form a large population of clones that will then differentiate

-

Most of the clones will develop into short-lived plasma cells that produce large quantities of specific antibody

-

A small proportion of clones will differentiate into long-lived memory cells that function to provide long-term immunity

Only one specific lymphocyte can be activated by a particular antigenic fragment to divide and form copies (this is called clonal selection)

-

However, a pathogen may contain multiple antigen fragments and hence activate multiple specific lymphocytes (this is called polyclonal activation)

B-Cell Activation

Each specific B cell exists within the body as a relatively small population of cells and must proliferate to form sufficient quantities to fight off infections

-

The activated B cells will divide via mitosis and then differentiate into short-lived plasma cells that produce large amounts of antibodies

Antibodies

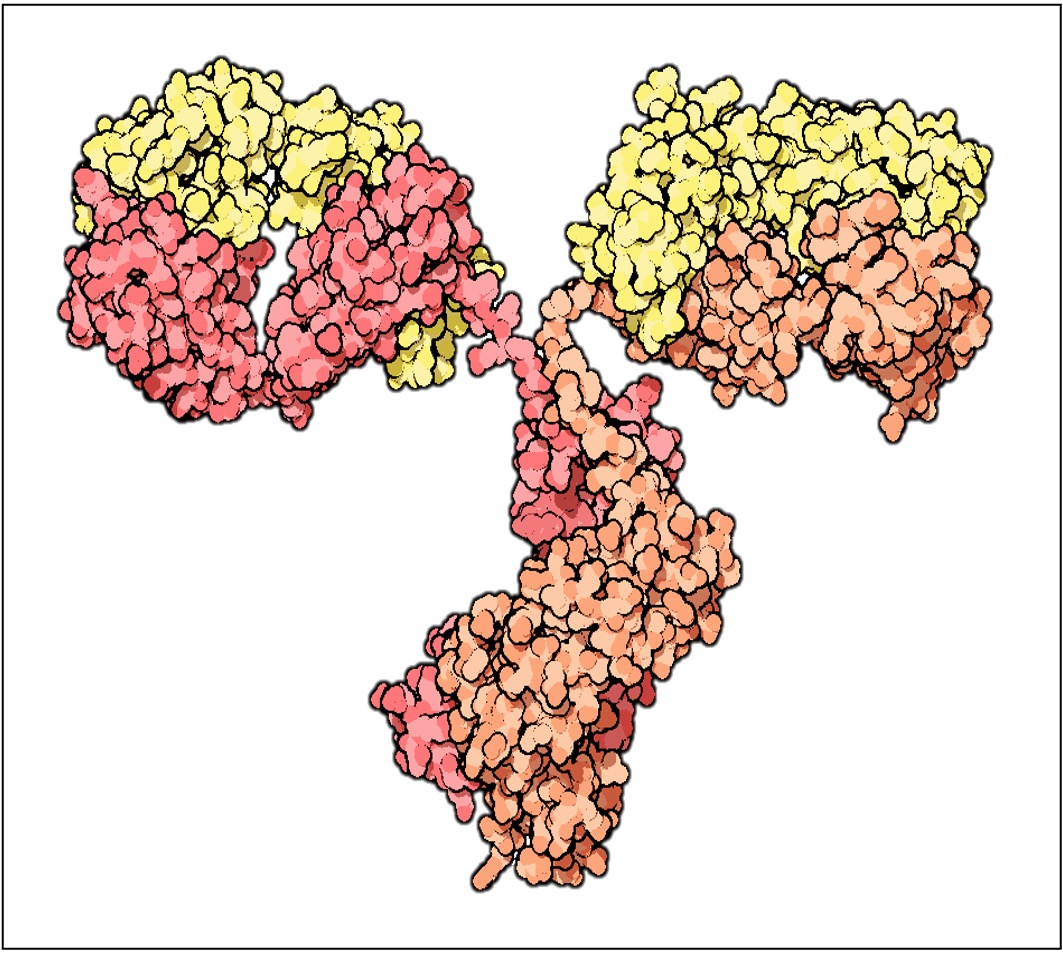

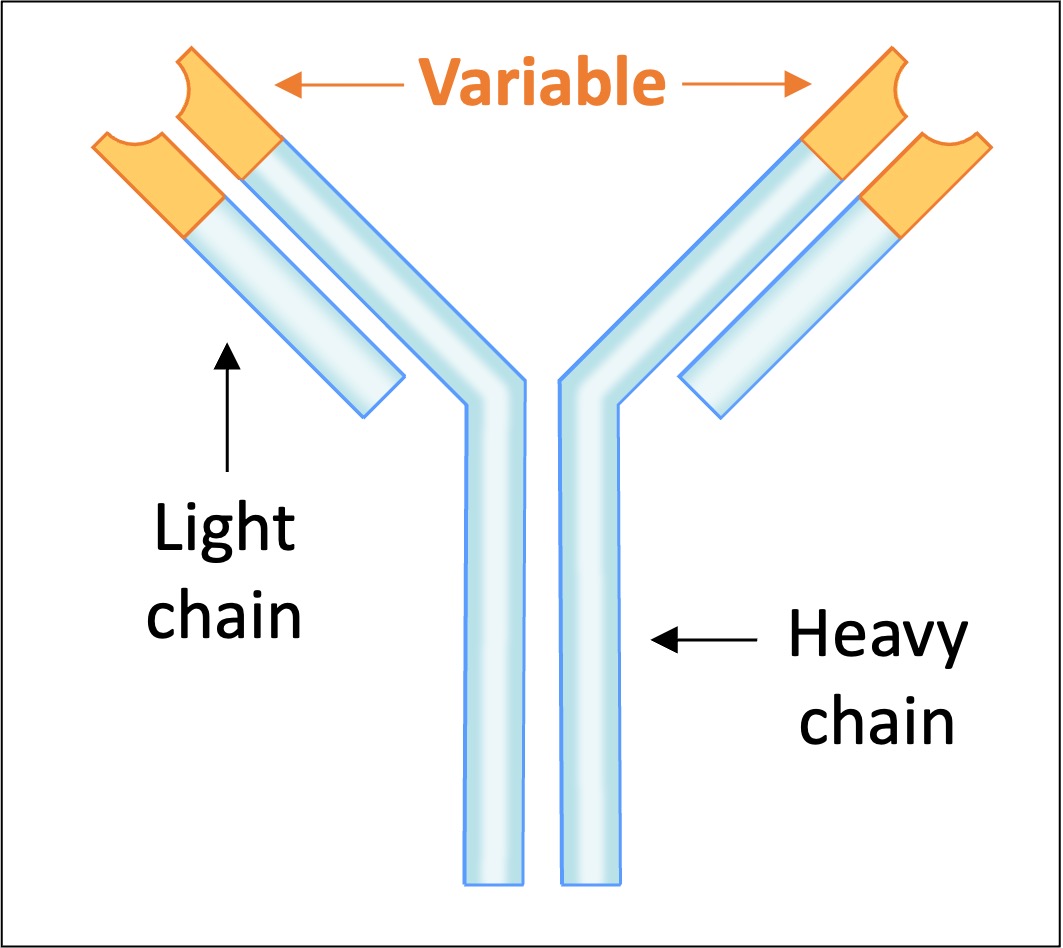

An antibody (or immunoglobulin) is a protein produced by B lymphocytes (and plasma cells) that is specific to a given antigen

-

Antibodies are made of 4 polypeptide chains that are joined together by disulphide bonds to form Y-shaped molecules

-

The ends of the arms are where the antigen binds – these areas are called the variable regions and differ between antibodies

-

The rest of the molecule is constant across all antibodies and serves as a recognition site for non-specific phagocytes (opsonisation)

-

Each type of antibody recognises a unique antigen, making antigen-antibody interactions specific (and part of adaptive immunity)

Antibodies enhance the immune response by aiding the detection and removal of pathogens by phagocytes

-

By coating the pathogen and making them easier to detect, the immune system can remove the pathogen from the body before disease symptoms can develop

Antibody Structure

Diagram